Here’s why this sale matters — and where it sits in Klimt’s larger body of work.

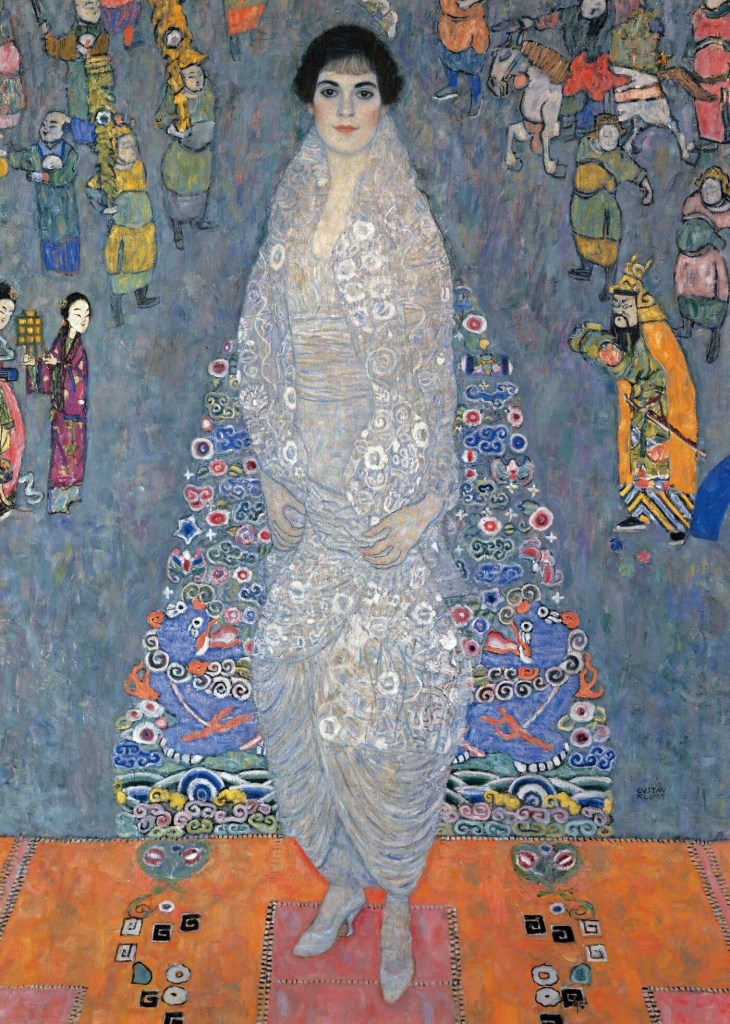

German: Bildnis Elisabeth Lederer (1914- 1916). Oil-on-canvas. 180.4 cm × 130.5 cm (71.0 in × 51.4 in)

Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer (shown above) sold at Sotheby’s New York on Tuesday, November 18th, 2025, for $236.4 million — now the highest price ever achieved for a Modern artwork at auction, and the priciest Klimt ever to cross the block.

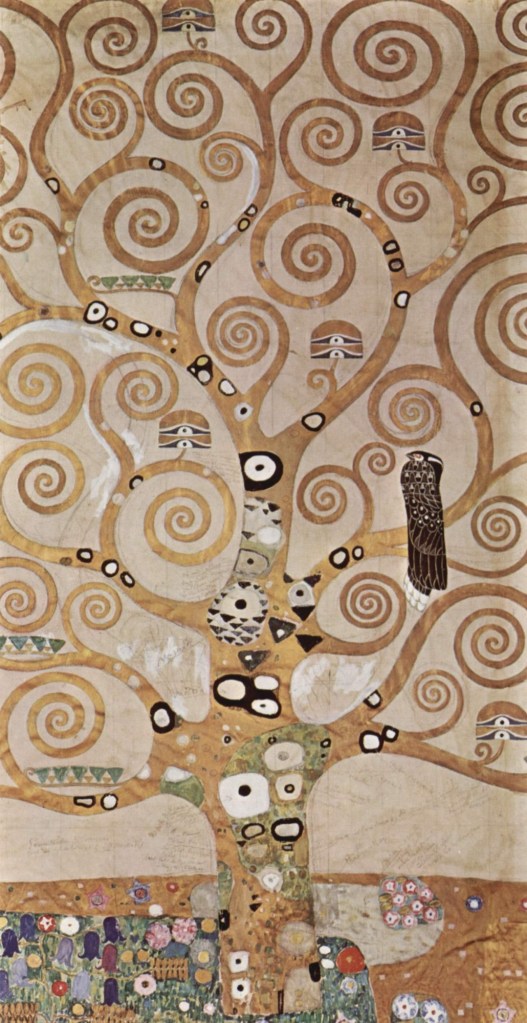

195 cm × 102 cm (77 in × 40 in).

Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna, Austria

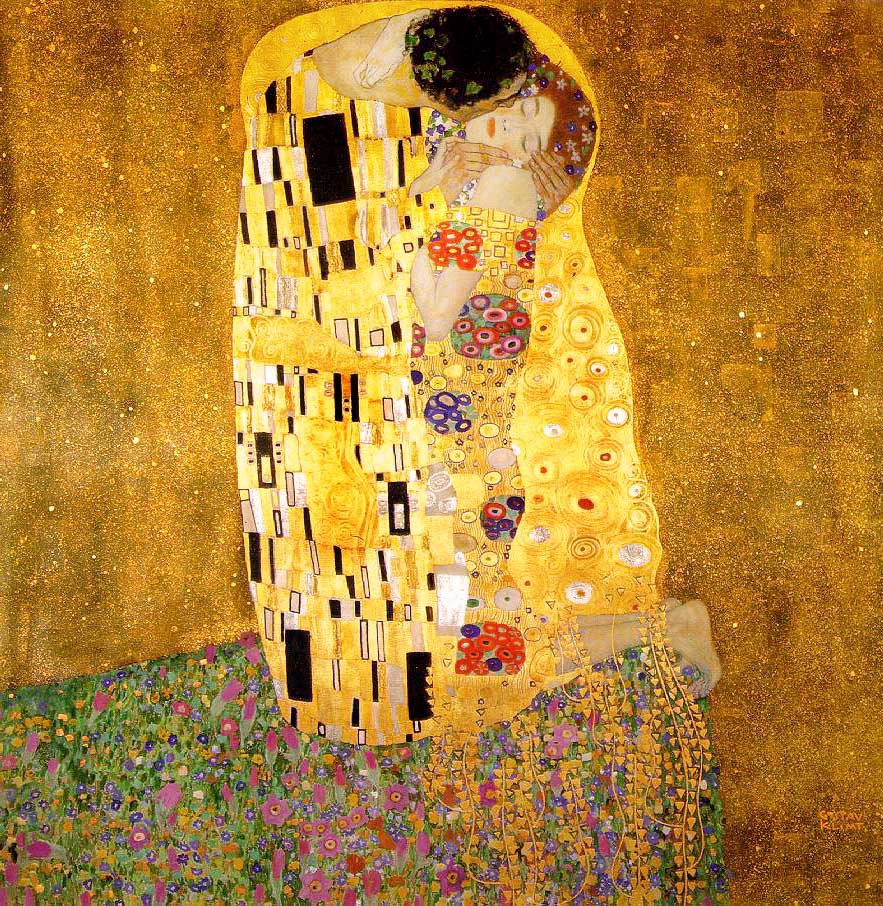

Klimt’s name is often attached to his icons — “The Tree of Life”, “The Kiss”, “The Maiden”, “Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I” which was the subject of a book and movie.

But ‘Elisabeth Lederer’ belongs to the quieter, more psychologically charged phase of his late career. Painted during the First World War, it shows a young Elisabeth Lederer wrapped in an almost weightless lace sheath, surrounded by a procession of figures that feel half-real, half-mythic. The background is where Klimt lets Vienna’s entire cultural atmosphere hum: colour-field, ornament, and dream logic woven together.

The sale isn’t just a market headline; it’s a reminder that Klimt’s late portraits still carry that unmistakable voltage — the mix of intimacy, decorative intelligence, and a kind of shimmering unreality that nobody else has ever replicated.

National Gallery Prague

And then there are Klimt’s landscapes — the quiet revolution

What often surprises people is that Klimt’s landscapes were never side projects. They were laboratories. While the portraits vibrate with ornament and psyche, the landscapes — Flower Garden, Avenue to Schloss Kammer Park, the lake scenes — let him push colour almost to abstraction. Square formats, dense surfaces, fields of flowers rendered as shimmering mosaics of pigment. They’re meditative and experimental at once: Klimt without the gold, without the society commissions, without the myths — just the eye, dissolving the world into pure pattern. Many collectors consider these works his most modern, and they’re increasingly recognized as precursors to later abstraction.

Moments like this remind us why Klimt still feels contemporary — that blend of ornament, atmosphere, and quiet strangeness hasn’t faded, not even in his landscapes.

Leave a reply to Anonymous Cancel reply