Yesterday morning, Saturday November 1st, during my daily call with my stepfather of over four decades known to many as T-Bear, I caught this screenshot of him with my beloved Stella Mia (shared with his permission). He spoils her with frequent walks and constant affection, often remarking on how intelligent she is.

I’m deeply grateful for my stepfathers unconditional support over this past year in particular, having lost my father on November 5th 2024.

Getting these regular glimpses of my sweet girl while I remain confined in conditions so far from ideal they feel closer to imprisonment than care—though I’ll add that several members of staff have shown genuine kindness, and that has mattered more than they may ever know.

I finally regained full use of my phone on Thursday, the day after my court appearance — not a minor development. For the past five weeks, since Dr. G returned from vacation and resumed oversight of my case (as she had during previous hospitalizations), I had been allowed to use it only four hours a day — two hours per shift — under her directive and the pretext that it was “too agitating for me.” She used the same justification during a two-week solitary confinement in 2021, imposed under COVID protocols, when she banned my phone altogether.

I never accepted those arbitrary restrictions, which cut me off from the outside world and prevented me from freely advocating for myself. Some staff were more lenient than others, allowing me to keep the phone despite the directive, even as a “priority” document was posted at centre of the front desk for all staff to see, logging my usage each day.

I wasn’t supposed to see that document, but I happened to catch a glimpse of it a couple of weeks ago — after which a few staff members quietly acknowledged its existence — it was even openly shown to me.

Dr. Z, my treating psychiatrist at the Allan Memorial Institute initiated the Request for a Community Treatment Order for 24 Months and served as the expert witness in court on Wednesday October 29th to argue that I was “completely detached from reality”—though he explicitly told me when the judge requested a pause in the proceedings that I had presented my arguments extremely well.

That shouldn’t have surprised him. I’ve always been articulate, composed, and far more coherent than the narratives all too many psychiatrists likes to impose on me. I accepted the compliment and replied that I enjoy public speaking and have never been intimidated by a courtroom.

After all, I’d spent six weeks preparing—meticulously studying his letter and every one of the eight psychiatric reports written by five different individuals.

Each report contained such glaring fabrications, errors, and distortions that dismantling them, almost surgically, was effortless. Which is fitting enough, considering I am the great-granddaughter of a Catholic heart surgeon on my mother’s side and a kosher butcher on my father’s.

On Wednesday morning, I decided to sleep in and get plenty of rest for the big day ahead. I’d been told my ride to the Montreal courthouse at 1 Notre-Dame Street would arrive at noon. My morning nurse came to wake me with a reminder to be ready—an unnecessary precaution, since my security escort and taxi arrived a full hour late, causing needless anxiety.

What should have been a fifteen-minute ride turned into a crawl through endless detours and heavy traffic, leaving me barely ten minutes to brief my lawyer upon arrival. The delays, the chaos, the rush—any of it could have rattled me, but when I settled into the taxi and noticed it was 1:11 p.m. on my phone as we pulled away from the hospital, I decided to stay composed.

For weeks I’ve been sleeping nine to eleven hours a night and eating well—putting a lie to their claim that I’ve been manic. In the final days before court, I focused on grounding myself and maintaining calm despite constant provocations (of which there are plenty on a psychiatric ward, believe me).

Life keeps throwing obstacles in my path, and I’ve learned to laugh in their face and stay centred when it truly matters. I’ve also learned, the hard way, that raising one’s voice is treated as a criminal act in this country—and that people often mistake a soft tone for kindness, as though volume determined intent.

Dr G., my psychiatrist at the Montreal General, who has known me since 2021, met with me on Thursday and gave me time to tell her how things had gone in court. I wasn’t surprised when she asked whether I wished to continue being followed by Dr Z., despite his deliberate falsifications in official documents and even in front of a judge.

As I quoted in the notes I took while he testified: “She told me in the ER that because she had survived a suicide attempt, she couldn’t die.” This is a lie, and I could never trust a doctor who would frame me as that disconnected from reality. Dr Z. has no appreciation for creative minds and has even discouraged me from publishing my memoirs, saying it would “upset my family”—the same family, I should add, that neglected me for most of my life. I simply do not feel safe with him, which is why I contacted the ombudsman’s office about him back in February.

During the hearing, I raised two issues psychiatrists and courts have persistently overlooked. First, I explained that I’ve been requesting an assessment for neurodivergence (also known as autism spectrum) since 2021.

It is increasingly recognized that autism and related profiles often present very differently in high-functioning females—particularly in post-menopausal women, who are only now being correctly diagnosed after decades of misunderstanding. The possibility that my so-called “manic traits” — including what is repeatedly described as “pressured speech” and “tangential thoughts” — could in fact reflect traits common among creatives, nonlinear thinkers, and gifted or neurodivergent women has never once been properly examined.

Second, I presented the possibility of witness tampering or professional bias—that certain psychiatric reports appear coordinated in tone and distortion, consistently reframing facts to portray me as psychotic. I pointed out that Dr Z. aligned himself early on with my maternal family’s discomfort over my decision to publish excerpts of my memoirs online, and that this personal disapproval may have influenced the narrative later repeated in other reports.

Dr G. and I agreed it would be best to find another psychiatrist—someone who will respect and encourage my creative process.

It still isn’t clear why Dr G. decided to lift the severe phone restrictions—a document treated as priority by staff—when I asked for normal access between 9:30 a.m. and 9 p.m., like most other patients. But the change has made a difference: it helps keep me occupied while I wait for the judge’s decision, expected tomorrow Monday, 3 November, on whether to approve or deny Dr Z.’s request to medicate me by force.

I was brought here by ambulance, unnecessarily strapped to a gurney after excessive police force and humiliation tactics were used, with two police escorts, under the false pretext that I was suicidal. I pleaded with them to contact my stepfather—who could have confirmed the claim was absurd—but they refused, even hanging up on him when I called as they were forcing me out of my apartment. That needless escalation, like so many I’ve experienced with the SPVM before, became the foundation for everything that followed.

In fact, a similar incident in 2021 was witnessed by journalist Ethan Cox, who later covered it in Ricochet under the headline “Police intervention highlights broken system for responding to mental-health crises.” The piece refers to me under the name Sarah and describes how officers escalated a situation that began with a severe migraine, ignoring a neighbour’s offer to bring me safely home to rest.

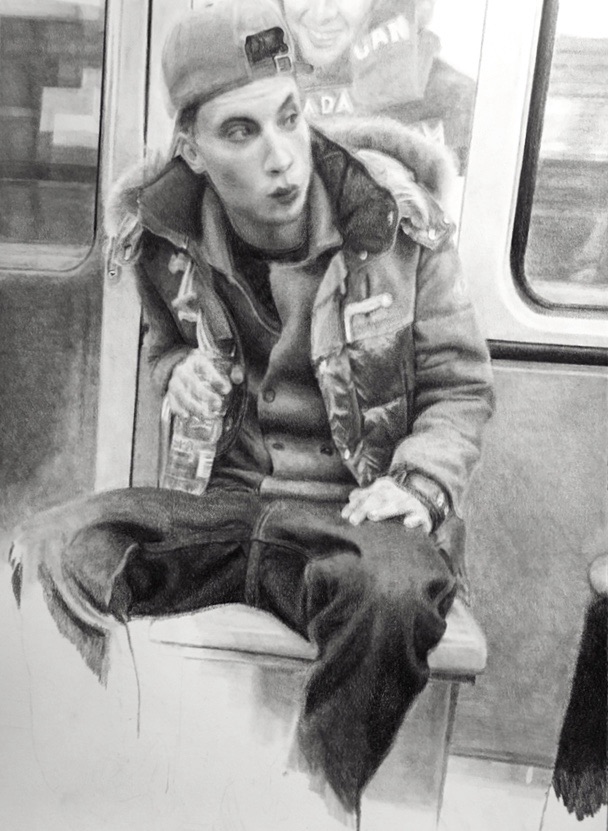

During our interview, Dr. G asked whether I had been drawing lately. I told her I hadn’t felt inclined—my writing serves me better these days. She pressed gently, asking why I don’t draw for personal satisfaction. The truth is that artmaking gives me very little pleasure; my inner critic is merciless, and unless true inspiration strikes, the process feels punishing rather than rewarding.

Graphite on paper, November 1, 2016.

As I finish editing this post on November 2, 2025 — which I began yesterday, exactly nine years to the day after completing this drawing — and following the last piece I finished in October 2022 (still untitled, drawn in ink, shown below), I’ve placed that project — and all artmaking — on hold. Visual expression has always been a gift, but it no longer brings solace.

Writing, however, remains my lifeline. I began journaling at nine, when my mother—herself a professional writer—placed a blank notebook in my hands and said, “I won’t be able to explain everything to you, but if you write everything down, it will eventually make sense.”

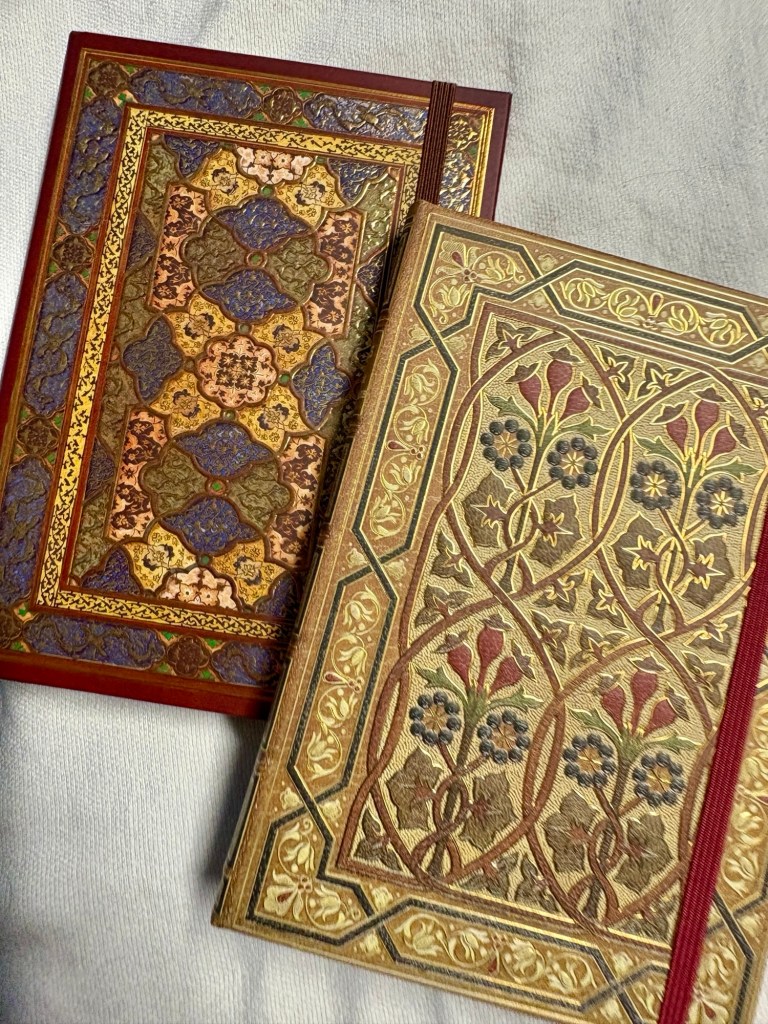

Forty-seven years later, confined under a court order that forbids me to leave the ward, I’m still writing to stay afloat—filling the beautiful Peter Pauper Press journals I was allowed to purchase at the hospital gift shop with a member of staff accompanying me.

Many of the psychiatric reports written about me contain outright inventions: as aforementioned, that I believe myself “immortal and unable to die,” or that “the Messiah told her to come to the ER” — words I have never uttered and beliefs I have never held.

Even so, several nurses and patient attendants have quietly told me they know I am neither manic nor psychotic. Some have hinted they sense something else is happening here. One male nurse even said he believed I would “crush it in court,” which was heartening to hear.

I therefore presented my case before the judge on 29 October 2025 with clarity and composure. He is an old-school jurist, and, according to my lawyer, usually rules immediately in favour of court-ordered medication. Yet this time he chose to take the entire weekend to deliberate and review the material my lawyer submitted — including a draft of my ombudsman report and a letter from my stepfather confirming what I have long asserted: that my mother told him, as she told me several times, that she electrocuted herself by cutting live wires with scissors while pregnant with me, and believed she had killed me when I stopped moving for hours.

That corroboration supports what I have said for years: that I live with Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (CPTSD) — a diagnosis psychiatrists have persistently refused to acknowledge, choosing instead to label me bipolar and (over) medicate me accordingly, despite the fact I’ve consented to psychiatric medication for over a quarter century, and it has never helped me.

Perhaps that’s because my brain chemistry was never the problem. Perhaps what I have needed all along is acknowledgment: to be believed when I say that trauma is real, that survivors don’t heal through suppression, and that justice requires holding abusers accountable instead of victimizing the same individuals again and again.

Maybe true treatment begins with that recognition.

Leave a reply to A hateful commenter Cancel reply