I woke up in the middle of the night to drink a sip of water and am fuming. Absolutely furious. I have no idea what I was dreaming about but I certainly do know what I’ve been posting about all over my socials over the weekend which—to sum it up in one sentence is—let me just be unapologetically ME.

I knew my call to a family member who has a deep need to control the narrative was going to be triggering for me yesterday. I tried to prepare myself for it but OMFG. I tried to stay calm, but it required a lot of emotional labour on my part.

Apparently I need to adapt because I risk alienating people. Risk alienating people? When has that NOT happened in my life? Apparently I’m not happy and will never BE happy if I don’t change something about myself and my way of communicating. I’ve always been told I need to soften my edges and blunt my message somewhat. But here’s a new one to me: I should focus on my goals and what my end game is.

So I tried to explain: I am my dearly departed father’s daughter. Nobody can ask me to change my nature. I’m an artist and a pure creative—I’ve always been more interested in the process itself than the end result. I embrace growth and change. That is the core of who I am. That is my essence and it will NEVER change. Why should I even have to explain that? To anyone?

Before that call took place, there were a couple of people who got in touch with me to chat and made not at all subtle comments about how I should focus on my visual art (subtext being my writing somehow doesn’t sit right with them). Which… fine, I’m SO GLAD you find my visual art worth engaging with, especially since one of you has amazingly good taste and has been running an awesome and inspiring online account filled to the brim with great content on artists and photographers from the 20th century while the other is a very talented artist with her own local art gallery and artist community… who has NEVER engaged online with me before and then not so subtly said to me “I express all of that in my artwork.” Good for you, AND?

Then there’s an elderly friend, in his late 90s who self-appointed himself as my mentor without asking how I actually felt about the matter when I initially showed him my drawings and has been not so subtly trying to influence me to pursue my “Renaissance master” drawing style as he thinks of it, ever since we first met last year. He sent me several emails this week, as he prepares for heart surgery, telling me I need to get back to my drawing and because I haven’t updated him on my life in the past few weeks, he has NO idea my mother and I have come to a permanent impasse and will definitely NOT be embracing each other in gentle mother/daughter affection anytime soon, or ever again.

He writes to me:

On a tumultuous stormy day when high winds and heavy snows close our sidewalks, our streets, making room for silence, welcome silence except for snow plows making a pitiful gesture to hold back nature’s assault.

In this tranquility I think of you, our exchanges, while you embraced your mother and the villages of France, while you reconciled with past stressful images, while you unfold “from this moment on.” How challenging! I do know that the Art within you, your creativity will be the ongoing source of delight, pleasure and glowing delight. I envisage your living in France, glowing.

Keep warm. I hug you.

I mean… “while you embraced your mother and the villages of France, while you reconciled with past stressful images”. How do I tell an elderly man about to go under the knife his most cherished and comforting thoughts on motherhood are being blown to smithereens as we speak? The irony is too painful to bear. 🙀

Then, let us not forget the looming pressure for a psychiatrist who could technically be my son—considering how young I was when I started being sexually active—telling me that I need to start taking antipsychotics because he’s made uncomfortable by my creative expression and has decided to take at face value the fact that my mother’s family members think I’m being manic because I’ve decided to speak my truth.

He seems to stick to this overcautious approach despite the fact that I’ve been followed by doctors from previous generations who recognized my genius and did not try to medicate it away. This particular shrink apparently never got the memo that creative expression is in and of itself the best medicine anyone could ever devise. But of course, big pharma has no way to monetize that and so doctors are not being taught how to engage with creative individuals other than trying to pathologise every single experience that is a normal part of what most people call just being a human being.

Countless people make the mistake of thinking they know me because I’m so transparent on the page. Countless people think they know how I lead my life, how I think, how I feel at any given moment because of whatever they’ve seen me posting on my socials last.

Interestingly enough, in this age of identity politics on steroids, nobody has ever actually asked me before “How do you identify Ilana?“. No. Instead they TELL me, a woman in my mid-50s how I SHOULD identify. How I SHOULD feel. How I SHOULD express myself. What tone I should use. What medium I should express myself in and on what platform it is or isn’t appropriate to do so.

Last year, I was graciously invited to spend a few days with some friends who live outside Montreal to spend the Christmas holidays with them. My dog, Stella Mia, was of course welcome too. Then one day, they decided to voice their annoyance with the fact that I choose English as my primary language. and had the gall to start criticizing the fact that I speak to Stella in English, that I post on my socials in English, the fact that I feel more comfortable with the English language at all. “You live in Québec Ilana, you were born here, we speak French in Quebec, you really should be speaking French, you’re à Québécoise, you should be proud of your national identity.”

EXCUSE ME?!?!? When I’m invited to people’s homes, I try my best to be a gracious guest and not engage in petty arguments, so I gently pushed back and said, perhaps you don’t understand that my mother taught me both English and French at the same time. They are both my mother tongues. Perhaps you don’t understand that I have dual citizenship as an Israeli and a Canadian and that I’m actually trilingual and consider myself as a citizen of the world. Perhaps you don’t understand that I’ve always communicated in English with my father. Perhaps you don’t understand that I actually think in English and dream in English—and maybe the fact that I’m more comfortable in English is my own business and not yours.

They had the gall to tell me what my identity is. They defined my identity as being Québécoise.

Oh really?!? I said I’m so very sorry, my dear friends, but you’ve known me for 30 years, I do not identify as Québécoise, I never have, and I never will and if you actually respect me, you won’t try to dictate what my identity should be. The absolute nerve of people who feel their entire identity is wrapped up in their sexuality telling me how I should identify—that I should have a nationalistic identity is so infuriating that I honestly wonder why I did not just pick up Stella right then and there and walk the 50 kilometres from their place to my home in downtown Montreal.

Then, after that conversation they actually made me sit through the Elvis movie in the French version. Despite it having been acclaimed (among other things) for how much like Elvis Presley Austin Butler sounds… I had to sit through that and pretend to listen to Tom Hanks dubbed over in French to avoid offending their precious sensibilities—and this although they understand English perfectly well but make it a point to refuse to engage with English content as a matter of cultural identity even when it makes no sense at all to do so. They were terribly offended that I spent that 2 hours and 39 minutes engaging with my phone instead. Too. Fucking. Bad. 😐

A few years ago during the pandemic we had a Canadian census to fill out and there was a question about how you “identified” and I thought well isn’t this interesting—let me have a little bit of fun, and so what did I write? I wrote cephalopod.

Yes. That’s right.

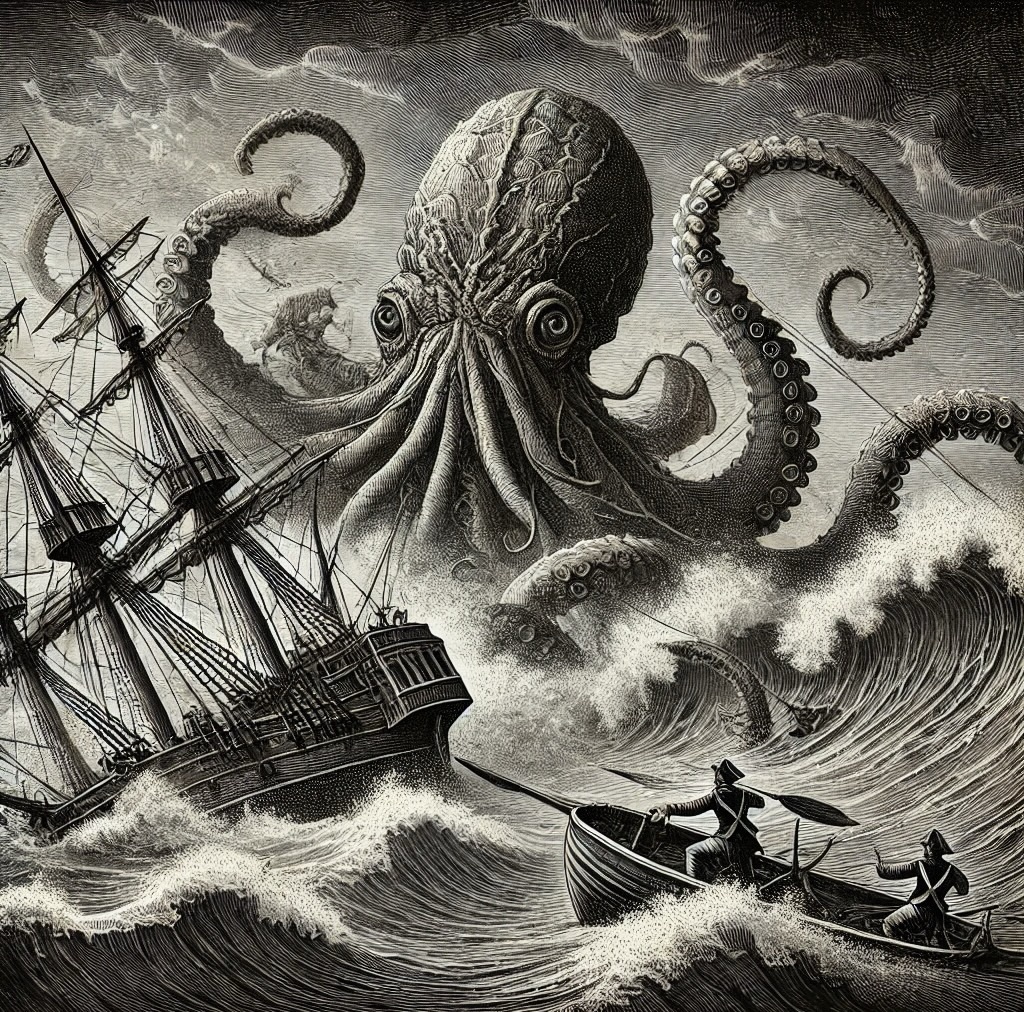

It was meant with tongue firmly in cheek because I think identity politics is nonsense. I followed that up with a TikTok, in which I said: I identify as a Kraken: a creature from the deep. I added some cool kraken graphics. Well wouldn’t you know some people who wanted to harm me weaponized that particular TikTok video against me and said look how unhinged she is—she actually thinks she’s an octopus. Of course they did.

Then people want to tell me the internet itself is the problem. That if I just stop posting online all my problems will go away. As if people only started being ridiculous and abusive when the internet became a thing. 🙄

If you haven’t watched My Octopus Teacher (2020) on Netflix yet, I heartily recommend it. I watched it shortly after it came out, but I had to break it up into segments because it was too overwhelming to take in all at once. The cinematography was sublime—the underwater world of the South African kelp forest so vivid, it felt like being submerged in another dimension. The music was haunting and tender, amplifying the sense of intimacy and wonder. That alone transported me, but the story itself? It made me cry and cry warm tears of recognition. I wonder, though, how many people who watched it identified with the octopus, as I did?

The documentary follows filmmaker Craig Foster, who, in the midst of a deep depression, finds solace and meaning by diving every day in the cold waters near his home in South Africa. There, he forms an unlikely bond with an octopus. This fragile, intelligent creature, living in a harsh underwater landscape of kelp forests, becomes his silent companion. Foster studies her daily life—how she hunts, hides, and plays—and in doing so, he finds his way out of his own darkness. The octopus teaches him about resilience, adaptation, and trust.

While many saw a man healing through nature, I couldn’t stop thinking about the octopus herself. She was more than an object of study or a symbol of healing—she was a sentient being navigating her world with uncanny intelligence and grace. Her life wasn’t an anecdote for someone else’s self-discovery; it was her own journey for survival, curiosity, and freedom. That’s what overwhelmed me. I identified with her.

Octopuses are astonishingly intelligent. Each of their arms has its own neural network, functioning almost independently, allowing them to problem-solve in real time. They can open jars from the inside, use coconut shells as portable shelters, and escape aquariums with such skill that it borders on magic. Their minds are alien to ours, but undeniably brilliant.

In My Octopus Teacher, the octopus’s brilliance is on full display—especially when faced with danger. When a shark begins to hunt her, she doesn’t panic. She gathers shells and rocks, creating a shield around herself, blending into the seabed. But the moment that struck me most deeply—the moment that made my heart pound—was when she did something completely unexpected when the shark became too menacing. Instead of fleeing, she latched onto the shark’s back, holding on as it thrashed, turning its strength into her escape. She didn’t just survive; she outwitted her predator. I felt that in my very bones.

Octopuses apparently have remarkably short lifespans, with most species living only about two years on average. This fleeting existence makes their intelligence even more astonishing—imagine cramming all that problem-solving ability, curiosity, and adaptability into such a short time.

In Sy Montgomery’s book The Soul of an Octopus, which I read in 2016, Montgomery explores the intricate minds and emotional lives of these creatures, describing their playful personalities, problem-solving skills, and the profound connections they can form with humans. One poignant detail is that a female octopus usually dies shortly after her eggs hatch. After devoting herself entirely to protecting and oxygenating her eggs, she succumbs to exhaustion, leaving behind a legacy of new life.

However, some cephalopods defy these norms. Older and larger individuals have occasionally been spotted—like the giant Pacific octopus, which can live up to five years, and colossal squids lurking in the deep waters of Antarctica. In 2007, a colossal squid measuring 10 metres was captured near New Zealand, and even larger specimens have been found in the stomachs of sperm whales. But these sightings are rare, and many believe they’re only scratching the surface.

The ocean’s depths remain largely unexplored—over 80% is still uncharted. If any creature could evade human detection, especially older, wiser individuals, it would be an octopus or a giant squid. Their intelligence, adaptability, and elusive nature make it entirely plausible that much older and larger cephalopods exist, hidden in the abyss, outwitting our clumsy attempts to find them. And maybe that’s exactly how they survive.

Since the dawn of time, humans have hunted, exploited, and pushed countless species to the brink of extinction—from majestic whales to the most fragile ecosystems. The whaling era alone nearly wiped out entire populations, driven by greed and an insatiable need to dominate nature. But what if some species, particularly those in the deep, outsmarted us by staying hidden?

The ocean has always been a source of both fear and fascination, giving rise to legends of monstrous sea creatures. The kraken, a mythical giant cephalopod, was said to drag entire ships to the depths, exacting revenge on those daring to intrude upon its domain. Stories from sailors across Scandinavia, the British Isles, and beyond spoke of colossal tentacles rising from the depths to crush and drown. Even the ancient Greeks had tales of the Scylla—a many-headed sea monster that devoured sailors who dared cross its waters.

Over time, modern science has tried to debunk these myths, attributing sightings to giant squids or misidentified marine life. As technology advanced, we convinced ourselves that these creatures belonged to folklore, not reality. But can we really be so sure? If history has taught us anything, it’s that humans are far more adept at destruction than discovery. We’ve mapped more of the surface of Mars than our own oceans. Why? Because the ocean’s depths are terrifyingly vast, dark, and unknowable. And perhaps that’s exactly why something as intelligent and elusive as a giant cephalopod would choose to remain hidden.

This taps directly into our subconscious minds—the part of us that fears what we cannot see or control. The kraken isn’t just a sea monster; it’s a manifestation of our deepest anxieties, our guilt for what we’ve done to the natural world, and our fear that something far older and wiser might one day rise to remind us that we’re not as dominant as we think.

For me, that connection to the subconscious is undeniable. Just as the kraken refuses to be seen until it chooses to strike, so much of who I am exists beneath the surface—misunderstood, unseen, and untamed. The ocean depths mirror the mind’s depths, where trauma, memory, and raw emotion swirl just below the surface. And every now and then, something rises from those depths, demanding to be acknowledged.

I have been both gifted and cursed in this life as a messenger of sorts. My mind has always freely navigated between worlds, between dimensions. They want to pathologize this because there is no frame of reference for my kind of intelligence. But what I do know is this: I have an uncanny ability to see through people. To immediately spot bullshit. And even when I’m trying to be gentle, kind, and careful, people feel seen—and exposed.

So what do they do? They instinctively recognize that the kraken is staring straight at them—the parts of their subconscious they’ve fought so desperately to control and push away. And that terrifies them. So they try to rein me in. Keep me small. Infantilize me. Dismiss me. Pretend I’m irrelevant. Anything to avoid facing their own fears.

But guess what? I exist. Here I am. My name is Ilana Shamir. My initials are IS—and I AM what I am. You can run away in terror, you can dismiss and ignore me or you can try to poke me, but if you do? Don’t be surprised if I squirt a bit of harmless ink in your face. And count yourself lucky I have self-control and never go full medieval kraken on anyone, however much they deserve it. 😐🐙

- Rebuilding the Codex Drawing Series

- How AI is Shifting our Language

- Marker Study No 2

- A Quiet Pencil Study

- Survivors

Leave a reply to Anonymous Cancel reply